Lesson 1

The Emergence of a Problem to The Immigration Reform and Control Act

Illegal immigration as a thorny political problem

Illegal immigration became a point of political controversy in the early 1970s as the number of irregular entries increased and media outlets and political pundits began focusing more intently on this uptick. It was hardly the first time that immigration became a touchstone of political debate, but the reasons for its emergence at this time, as with other times it became a flashpoint, were partly attributable to distinct features of that period. Two examples in particular are worth highlighting for illustrative purposes here: the elimination of the Bracero program and the introduction of an annual Western Hemisphere cap on legal entrants. The first closed off an existing legal avenue for migration and the other curtailed the number of migrants allowed into the United States on annual basis.

While an exploitative and often inhumane system that was long opposed by Catholic leadership in the United States, the Bracero program was first implemented in 1942 in response to shortages in agricultural labor due to World War II, officially ended in 1964, and not replaced by an alternative system that could respond to labor demands on both sides of the border. Setting aside the problematic nature of the program as structured, during its decades long existence it created a mechanism through which migrant workers could enter the United States for seasonal work, earn more money than they were able to do in Mexico, and return home at the end of their employment commitments. While the program was officially ended in 1964, the demand for seasonal work remained but the legal avenues to do so did not. Many individuals who had formerly partaken in the system had an ongoing, economic interest in continuing seasonal work, businesses that had formerly employed them did as well, and government authorities often turned a blind eye. Existing channels effectively remained in place, although the provision of migrant labor through these channels were often no longer conducted in a legal fashion. (Massey, 2012)

The implementation of an annual Western Hemisphere cap was a second contributing factor to the rise of illegal immigration. Prior to 1965, countries in the western hemisphere (e.g., Mexico, Canada, etc.) did not have any numerical limits on the number of persons who could migrate to the United States in a given year, although various qualitative limits remained in place. With the passage of the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act, Congress for the first time set an annual cap of 120,000 visas available for immigrants from Western Hemisphere countries. This meant that the maximum number of visas issued per year to countries in the Western Hemisphere could not exceed this limit, although immediate family members of US citizens (e.g., spouses, minor children) were exempt.

In 1976, Congress further established a 20,000-person annual limit for each country in the Western Hemisphere. One consequence of the cap was that the demand for visas regularly outstripped supply, thus leading to lengthy waiting periods. These caps, in turn, increased the likelihood that a person who wanted to find work or reunite with family in the United States, but could not secure a visa, would enter the country illegally.

Letter from Bishop James Rausch, General Secretary of NCCB/USCC, to all the bishops regarding proposals related to the Western Hemisphere cap, August 1975.

In response to an early version of this legislation, Bishop James Rausch, General Secretary of National Conference of Catholic Bishops/United States Catholic Conference (NCCB/USCC), addressed a letter to all the Catholic bishops of the United States expressing concern about the proposed 20,000 per country cap. He noted that in 1972, non-family related preference entrants from Mexico amounted to 41,707, most of which pertained to family reunification. He lamented that “a cut of 50% in this movement will have a devastating affect on the families involved and would be a basic departure from the philosophy of family reunification, which is the foundation of our present immigration law.”

Although similar limitations were imposed on Eastern Hemisphere countries, geographical proximity to the United States of countries in the Western Hemisphere made efforts to circumvent these limits easier. In short, closing off avenues through which people could migrate either temporarily for work or permanently with a view to family reunification, what followed was an increase in irregular migration (Migration Policy Institute, 2015). In 1964 there were an estimated 29,366 unauthorized admissions; by 1977 that number had increased to 464,100.

In response to this increase in irregular migration, Congressional leadership in the House Judiciary proposed legislation during the 92nd (1971-1972) 93rd (1973-1974) and 94th (1975-1976) Congresses that sought to provide a solution to this increase in unauthorized migration. These legislative proposals relied heavily on the use of employer sanctions, which aimed to deter employers from hiring individuals without status; of secondary concern was the question of what to do with the millions of unauthorized migrants and their families who were living in the United States. Having long advocated in support of migrant protections and given the expansive social service outreach programs geared to incoming migrant populations, the Church was understandably concerned any effort to respond to this issue that might prove detrimental to these populations.

The United States Catholic Conference Responds

In March 1975, Msgr. George Higgins, then Secretary for Research at the United States Catholic Conference, testified before the Judiciary’s Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and International Labor in response to the introduction of H.R. 982. As with other proposals of this period, the primary thrust of this legislation aimed at dealing with illegal immigration by imposing sanctions on employers who knowingly hired individuals not qualified to work in the United States.

Higgins’ testimony is largely representative of the way in which the bishops approached the migration issue at this time and highlights key themes that would be central to their advocacy work in the coming decades. Some of the positions taken were a reiteration of positions long held and others getting clarity and more finely honed in later years.

While acknowledging that enforcement mechanisms have a role in immigration policy, Higgins noted that enforcement alone would not stop the increase in illegal immigration since it failed to address the key issues that drove migration in the first place. Nor were there currently in place existing policies that effectively dealt with the unauthorized population currently living in the United States. It was critical to address these issues simultaneously and not piecemeal.

Concerning the key issues that drove migration, Higgins highlighted two central factors. First, for too long the U.S. had provided deficient forms of foreign aid to Latin America and supported unjust economic policies there that exacerbated the conditions driving illegal migration. To rectify this problem, he suggested increasing foreign aid to America’s southern neighbors, assuming this would help mitigate the economic causes contributing to the outflux. Second, he accused the U.S. government of being complicit in the problem of illegal immigration; blame and punishments associated with illegal entries should not be placed solely on the migrant who crossed illegally but also on those who directly or indirectly supported such crossings. Higgins noted that “because of our failure to prevent the mass influx of illegal aliens and our failure to enforce existing laws, the government of the United States bears a heavy share of responsibility for the chaotic situation which exists today.” For this reason, people who cross the border illegally should not bear the full burden of blame for the current situation.

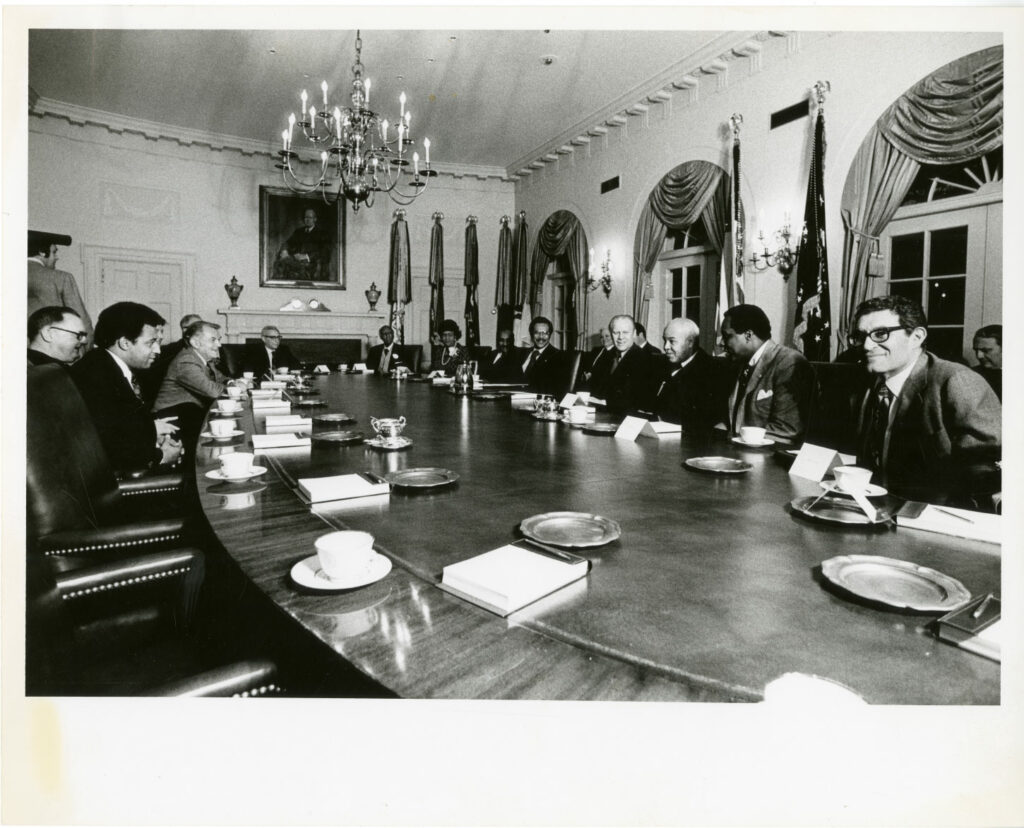

Msgr. Higgins (far left) with Gerald Ford, Henry Kissinger, and others in the meeting room of the White House, 1975. American Catholic History Archives/The Catholic University of America (ACHR-CUA)

Higgins suggested that with several million people currently living and working in the United States in unauthorized status, an “across the board amnesty” (amnesty was typically the preferred term used throughout this period) should be offered; failing to do so risked driving those living in the United States illegally further underground and creating an established, vulnerable subclass of people. Any enforcement efforts should be prospective and not retroactively applied, thus responding to potential future waves of unauthorized migration and not upending the lives of millions of those currently present. In the judgment of the USCC, applying enforcement measures retroactively absent an opportunity to adjust status absent an amnesty would likely lead to “unbelievable havoc” and widespread family separation. It would be, declared Higgins, “unconscionable that our government should even consider separating families by forcing a mass exodus or deportation of literally millions of men, women, and children.”

In response to an inquiry from Rep. Joshua Eilberg (D-PA) regarding the possibility of a tailored amnesty that would consider a more “case-by-case” approach based on factors like employment history, length of residence, family ties, etc., Msgr. Higgins turned to his colleague Donald Hohl, Associate Director of Migration and Refugee Services, for an answer. Hohl noted that the USCC’s support for an across-the-board amnesty was “especially, but not solely, for the purpose of family reunion. This is the primary basic concern of the Church.” As will become apparent in future modules, the emphasis on family unity is a key theme in the institutional church’s effort to support migrant communities and one that stretches across decades of engagement on this issue. Such an emphasis highlights the primary role that families play in the maintenance and well being of every society.

At the end of the Congressional terms H.R. 982 had failed to secure passage and alternative proposals offered in subsequent Congresses also failed to gain traction. It was only in the following decade that immigration reform finally became politically viable and a compromise was reached that allowed for a tentative solution for this issue to become a reality.